Early days…

Joe began his photographic career in 1980 after completing a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Reading University. He spent the next four years assisting photographers in Washington DC and London, on location and in the studio. From the mid-1980s, Joe worked freelance in London doing portraits, studio and commercial work, and tourist imagery.

Books, and travel, and books

1987 brought the first book commission: The Founders of the National Trust (Graham Murphy, author), for publisher Christopher Helm. In 1988, the Trust commissioned Joe directly for the book, In Search of Neptune (Charlie Pye-Smith, author), a study of the Trusts’s coastal properties.

In succeeding years, Joe travelled widely through western Europe doing dozens of travel guides and coffee table travel books. Publishers included Christopher Helm, George Phillip and Dorling Kindersley. He joined Charlie Waite’s stock photo-library, Landscape Only, and then Tony Stone Worldwide/Getty Images.

Joe’s goals were completely re-set after working as expedition photographer for Raleigh International in Alaska during the summer of 1991. That experience inspired his belief in the importance of preserving wilderness and wild land globally.

Landscape photography soon became his focus, at around the same time as Joe moved to North Yorkshire in 1993.

Having worked consistently on landscape in the north of England, Scotland and beyond for several years, Joe was asked by Eddie Ephraums, the commissioning editor at Aurum/Argentum, to write a book on his photographic practice, which led to the publication of First Light in 2003. He also wrote Scotland’s Coast (2005) and Scotland’s Mountains (2009) for the same publisher; and, for publisher Francis Lincoln, The Northumberland Coast (2008) and This Land (2016; author Roly Smith). Capability Brown (2016) and Humphry Repton (2021) are collaborations with author John Phibbs, and were commissioned by New York publisher, Rizzoli.

Two major exhibitions led to the self-publication of two more books in 2022. Woodland Sanctuary was a collaboration with photographer Simon Baxter. Simon and Joe’s exhibition of that name was a curated collection of woodland images in nine key themes, shown in the North York Moors Danby centre through the summer of 2022. Still Time to Wonder was a book based on Joe’s solo exhibition held at various sites around the Fountains Abbey estate in 2022/23.

National Trust

From 1988 until 2016, Joe fulfilled dozens of National Trust photo-library commissions, and this work appeared in the Trust magazine, many Trust books, posters, information panels and brochures, and indirectly for numerous conservation charities like the Woodland Trust.

Joe later worked on two parallel artist-in-residence commissions: one for the National Trust, on the Fountains Abbey and Studley Royal World Heritage Site; and the other at Brimham Rocks above Nidderdale (also for the NT). Joe was asked to respond to these landscapes creatively and produce print exhibitions as part of the Trust’s public arts programme. The work took place over almost three years, from 2019. The Brimham Rocks show was displayed at the Brimham Visitor Centre through the Summer and Autumn of 2021. The Fountains Abbey exhibition opened in April 2022 and was extended until March 2023 due to popular demand.

In 2025, he was commissioned to present an exhibition at Nunnington Hall for the Autumn season.

Workshops and tours

Joe led his first workshop in 1997, for Charlie Waite’s company, Light and Land. He continues to lead workshops, often in collaboration with fellow photographers including David Ward, Anthony Spencer, Alex Nail, Mark Littlejohn and Daniel Bergmann. Most of these have been in England, Scotland and Wales, with a few abroad as well, especially in the US desert south-west.

Joe has also worked in the polar regions with Mark Carwardine on tours in Antarctica; and in the Arctic to Baffin Island, Wrangel Island, Svalbard, and on the renowned North Atlantic Adventure expedition ship voyages. Joe has co-led small ship expeditions in Svalbard and East Greenland with Tony Spencer, and in Svalbard with Daniel Bergmann and David Ward.

He has given countless talks to camera clubs and societies from the early 1990s. Although based on his own career, images and life experience, they cover a broad spectrum of associated themes, especially focussed on habitat restoration and climate change, and also landscape photography’s relationship with other arts, including music, painting, sculpture, architecture, poetry and dance.

Printing

Joe prints all his own work and has also printed exhibitions for other photographers including David Ward, Anna Booth, Mark Littlejohn, Lucy Saggers, Simon Baxter and Kate Somervell. He teaches digital post-production, editing and printing, and leads workshops on printing for the paper and ink supplier, Fotospeed.

On Landscape

In 2010, Joe supported Tim Parkin in creating On Landscape magazine, a web publication devoted to promoting the art of landscape photography and its inspiration in (and dependence on) the natural world. Tim and Charlotte Parkin now run On Landscape independently, but Joe remains a close friend and regular contributor to the magazine.

The following article gives a third part summary of the genesis of On Landscape: https://www.lensandapen.com/monologue/on-on-landscape

Understanding Photography NHM

Joe was a judge for the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition at the Natural History Museum in 2011, and hosted associated events each year at the NHM for several succeeding years. These introduced the work, ideas and techniques of some of the competition winners to a live audience in one of the theatres at the NHM.

Joe Cornish Gallery

With friends Joni Essex, Joe Essex and Lizzie Johnston, Joe started a publishing and gallery business in 1999. Initially based in Stokesley, it moved to Register House in Northallerton in October 2004. The gallery developed into a largely community- based space showing the work of numerous photographers, and housed a popular cafe.

After a well-received collaborative exhibition featuring David Ward’s brilliant photography (Creative Parallels), and a final sale, the gallery business closed its doors for the last time at the end of 2023.

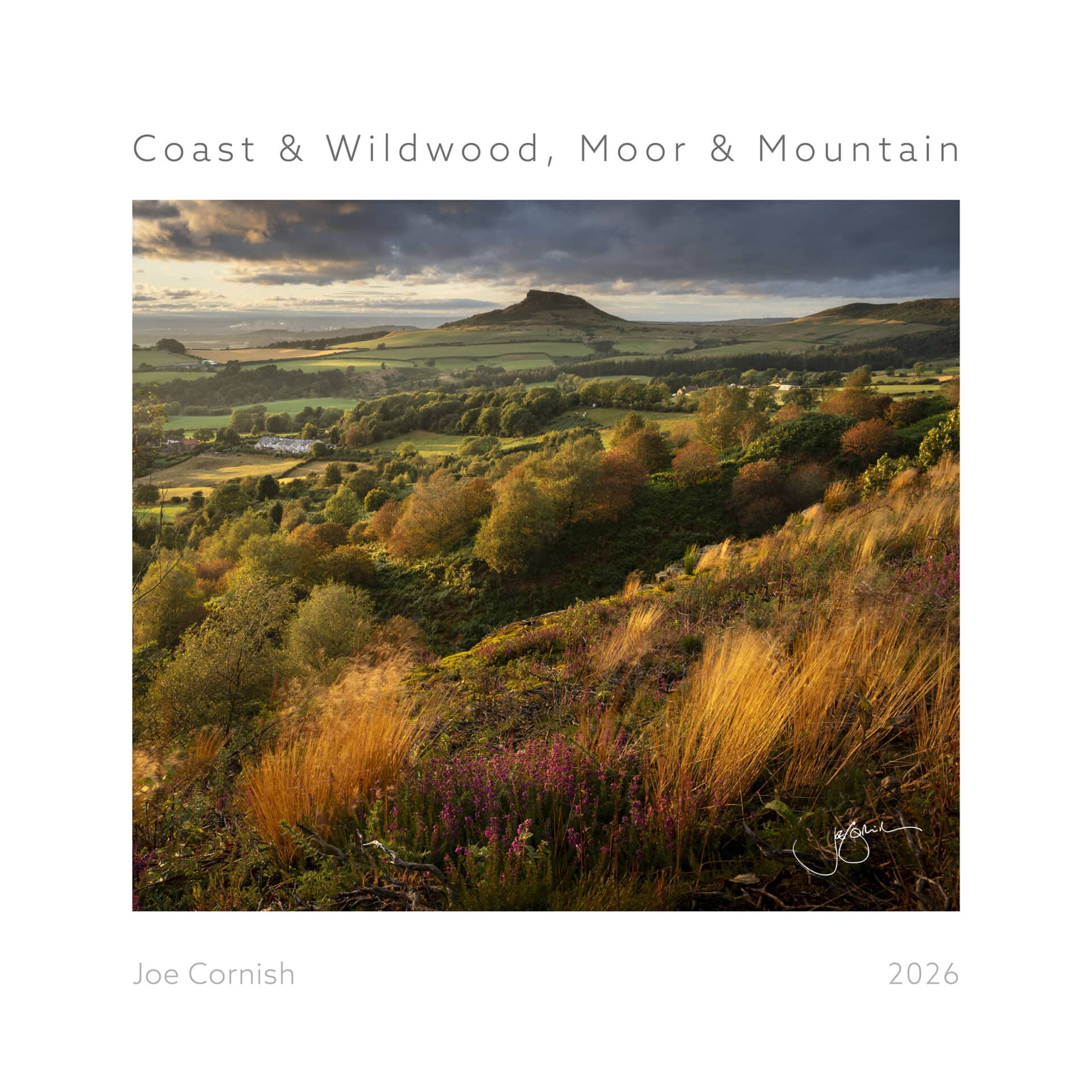

Calendar

Joe’s calendar was first published in 1998 and continues to today. Titled Northern Light for the first time in 2000, it championed the landscapes of northern England, occasionally including some historic buildings.

Its geographic range has now widened, and it is currently titled: Coast and Wildwood, Moor and Mountain. Published by Johnsons of Nantwich, the calendar is renowned for exceptional image and print quality.

Recognition

The Amateur Photographer magazine awarded Joe the Power of Photography Award in 2007 in recognition of his contribution to landscape photography.

In 2008, he was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society for his contributions to landscape photography and environmental awareness. Joe is an active supporter of the RPS as a Distinctions panel member. He became the first Chair of the RPS Landscape Distinction, which began in 2019, and still serves as an assessor.

In 2010, he was named One of the World’s 40 most influential nature photographers, by Outdoor Photography magazine.

Joe served for six years as a trustee of the North York Moors Trust. He holds workshops in support of the Trust each year.

The meaning of Wilderness

“In 1991, I was invited to be the official photographer on a Raleigh International expedition to Alaska. I had long dreamed of wilderness and, as a result of my travels in the US, of visiting its outlying northernmost state. I had skied in European mountain ranges, travelled and hiked in the South Island of New Zealand, and spent time in some of America’s great national parks. But I knew Alaska was different, “the final frontier,” the last continental-scale American wilderness. What an opportunity! I jumped at the chance.

Parts of Alaska are populated, notably Anchorage, and there are commercial industries, but you don’t travel too far before the expanse of wilderness swallows you up.

Most of my fellow Raleigh expeditioners (which included yet-to-become-astronaut Tim Peake) were – without exception – adventurous and excited to be in Alaska. The shared community of youthful enthusiasts and the experience of climbing, walking, standing – being – where it felt as if no-one had been before made the wild world feel like the only reality that mattered. The impact of this wildness was mind- blowing for us all.

Grizzly bear attack stories are a staple conversation in Anchorage bars. Fortunately, and although we saw plenty of wildlife, our bear encounters only happened while we were in the relative safety of our kayaks. We also came close to orca and humpback whales, and saw eagles soaring. Experiencing nature that is wild, free- roaming, beautiful and dangerous only deepened the experience, especially for us coming from the islands of Britain, with its complete absence of wild animal hazards.

One day on that kayak-borne journey I had time to wander alone up a gentle hill on an island in Prince William Sound. Across the sea, from below the horizon, rose snow-capped mountains. A small stream slipped like liquid crystal between rocks and over mossy ground. Trees, plants, wildflowers prospered in the sub-Arctic summer, fed by sunlight and rain, arranged by soil type, underlying geology, slope profile, aspect and drainage. Every living thing had its place in a dynamic, complex web of inter-relationships created by time in this unplanned garden. It seemed so effortless; an idyll unseen (mostly) by humans, a sanctuary for wild creatures.

Everything seemed and felt … just right; and to my eyes at least, nothing could have been more beautiful.

All that was growing had emerged since the retreat of the glaciers, some of which still reached the sea not far away. This dynamic evolution, countless years in the making, came as a revelation. This ancient wilderness was a glimpse of some original Eden. Since that day, Beauty and Wilderness have been locked together in my imagination. I was hooked. A wilderness addict. In my mind, the very essence and meaning of life had been redefined, reset, recalibrated.

I know my perspective was biased, idealised, immature. Since then, I have thought more about what ‘original Eden’ might mean. To those who lived before the agrarian revolution, a life of hunter/gathering may not have seemed idyllic, especially in harsh conditions. Nevertheless, real wilderness gives us a faint glimpse of a time when our human ancestors lived with nature, as a part of it.

We wouldn’t want to revert to a time before antibiotics and so much else, but we nevertheless need a new way of living with nature. Today, we exploit, destroy, or simply neglect the wild world, having never learned that we are still utterly dependent on nature to provide everything that makes our lives possible, as individuals, communities, economies and nations.

It was difficult to return home, holding these special experiences close to my heart, wanting to preserve that connection with the wild in some real way. In the years that followed, life went on, including most importantly the arrival of a family for me and Jenny. But my appreciation of the significance of wilderness has never diminished. I have tried to return to wilderness when I could since, although these trips are often far apart, and can come with the major guilty question mark of a personal carbon footprint due to flights.

In my political view of landscape, I remain a romantic. My heart sinks at the sight of extractive agriculture; of land stripped of nature, over-worked , poisoned by toxins (better known as herbicides and pesticides) designed to kill everything that might compromise short-term, intensive production, and polluting waterways with runoff soils and excessive nutrients. The prospect of thousands of hectares of industrialised forestry, the fate of land across large parts of Europe, provokes that same sinking feeling. Exploitation and degradation of land has only accelerated on every continent with human expansion and development since that journey to Alaska in 1991. At the same time, efforts at conservation and restoration are growing, but are a mere fraction of the scale of land that is over-exploited.

Still, I am grateful to live in the UK, a country that has wonderful terrain and climate. Britain’s landscapes and biodiversity have inspired artists, poets, composers and photographers for hundreds of years. The cycles of life and season remind us of the abundance and resilience of natural flora and wild creatures. Unpredictable weather provides an endless and enjoyable artistic challenge.

While ecological damage continues (due to industry, urban sprawl, intensive farming, and social and political apathy), hundreds of campaigning organisations have protected species and habitats, and ensured access so it can be enjoyed and experienced by many. Woodland particularly is returning, with native trees being protected and planted, and appreciated as never before. Marginal landscapes, coast and mountains provide habitat where some wild animals and birds can be accommodated on our crowded islands.

All that is remarkable and positive. But a few eagles in the air and orcas off-shore cannot hide the fact that Britain’s landscape supports no major, non-human predators. In biodiversity terms, we may have the shallowest ecosystem of any major nation.

Those inspirational months in Alaska still haunt and guide my critical observations of landscape. I know the reasons for wilderness retreat. Human migration and expansion, over tens of thousands of years, has populated all the most habitable regions of the planet, pushing wild animals and places to the brink.

To many, no doubt it seems that advocacy for wilderness preservation is an irrelevance. But the nature and climate crises make it more relevant than ever before.

My intuitive self has drawn its conclusions and I am stuck with them. My heart feels there must be another way, where we cherish, respect, revere and protect all that is wild, all that is left, and restore what once was. I believe the only future that will work for people will involve preserving nature’s wild remnants and restoring degraded landscapes.

We must learn to see that it is in our interests to share this unique, life-supporting wonder planet with the millions of animal species who have as much right to be here as we do; to preserve remaining wilderness, and to restore and live with nature, not against it. We must learn that respecting the rights of wild creatures for whom it is home is also to preserve our sense of what it means to be fully human, for now, and for all future generations.”

JC April 2025

Camera format evolution

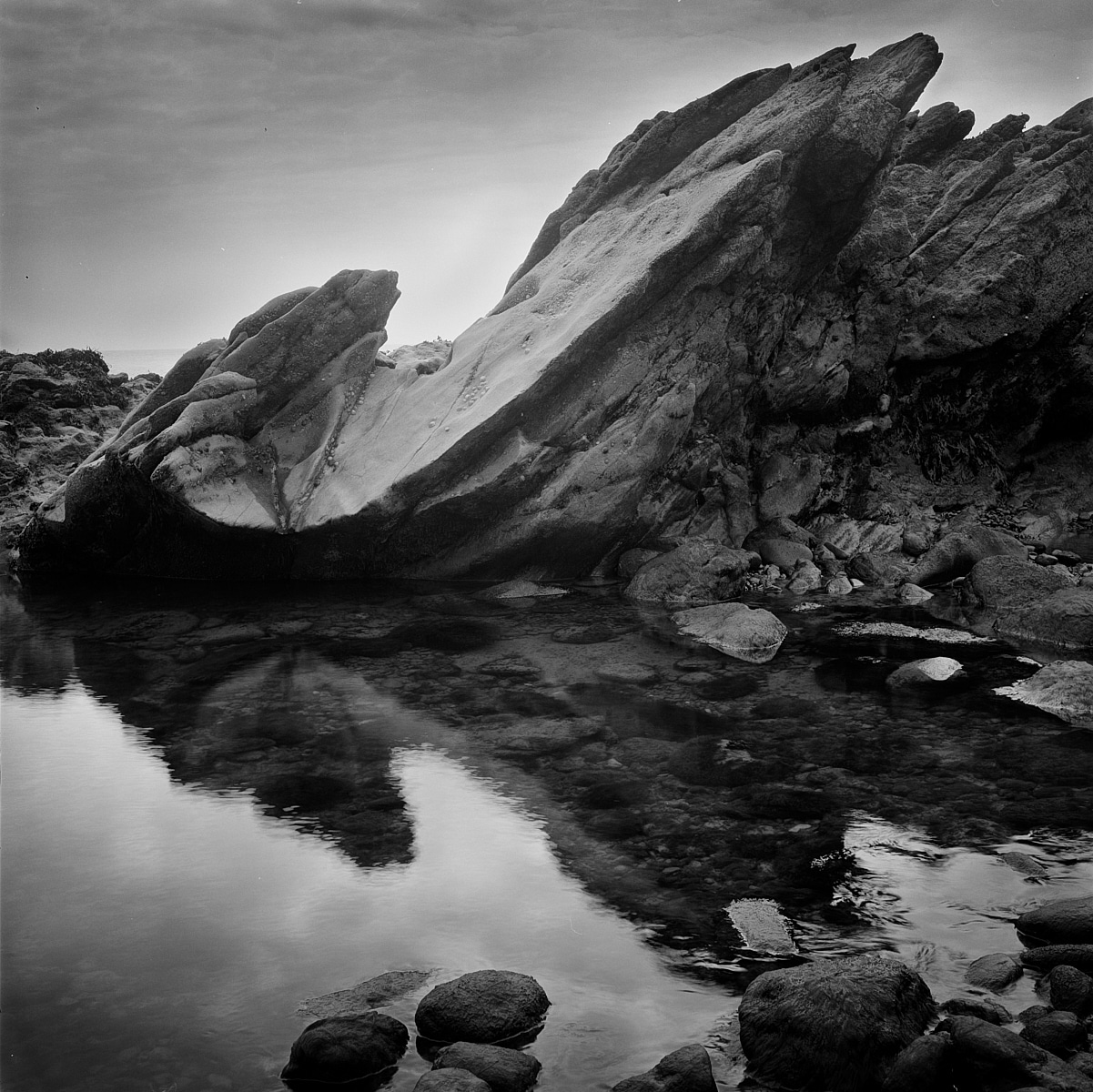

Through the 1980s and ‘90s, Joe shot mainly with 35mm and 6×6 cm cameras; also 6×7, 6×9 and 6×12 cm. He was an early adopter of Fujifilm transparency films (in spite of the market dominance of Kodak).

From 1998, he worked exclusively with large format 5×4 inch film cameras and Fuji Velvia and Provia transparency film; this formula was critical in the evolution of a “get-it-right-in-camera” approach and philosophy to photographic craft.

From 1999, scanning became an inevitable stepping stone in the transition to digital, and digital inkjet printing was added in 2005. In 2008 Joe adopted medium format digital using a technical field camera, aiming to preserve the control, depth and detail of large format film, but in a direct to digital workflow. The first combination was a Phase One P-45+ digital back, mounted on a Linhof Techno field camera, with high resolution Rodenstock lenses.

Current camera equipment:

Medium format digital: Phase One IQ4-150, used on:

Linhof Techno view camera, with:

Rodenstock lenses: 40mm Digaron-W; 50mm Digaron-W; 70mm Digaron-W; Nikkor- W 105mm; Rodenstock Sironar-S 150mm.

– or –

Alpa STC compact technical camera, tilt adapter. Rodenstock lenses: 35mm HR- Digaron; 40mm Digaron-W; 70mm Digaron-W;

35mm mirrorless interchangeable lens camera:

Sony A7rIV, Sony A7rV

Sigma Lenses: Contemporary lenses 24mm f/2; 35mm f/2; 50mm f/2; 65mm f/2; 90mm f/2.8; Art lenses 135mm f/1.8; 28-45mm f/1.8 zoom; Sport 500mm f/5.6 **

Lee Filters. Usual Lee filters system includes 7 or 8 Neutral Density graduates, polariser, and ND standards, four stop and six stop. **

Fotospeed. Favourite papers include Fotospeed’s fine art matte papers, Platinum Cotton 305 and Smooth Cotton 300. **

f-Stop: Currently Joe uses a Shinn 80 litre backpack for the Phase One/Linhof Techno, and expeditions; and an Ajna 35 litre for the Alpa STC and Sony/Sigma systems. **

** Joe is an ambassador for Sigma, Lee, Fotospeed, and f-Stop.